COMMERCIAL & PUBLIC LAW – Dealing with the Stock Exchange’s Delisting Decisions: Webinar Highlights

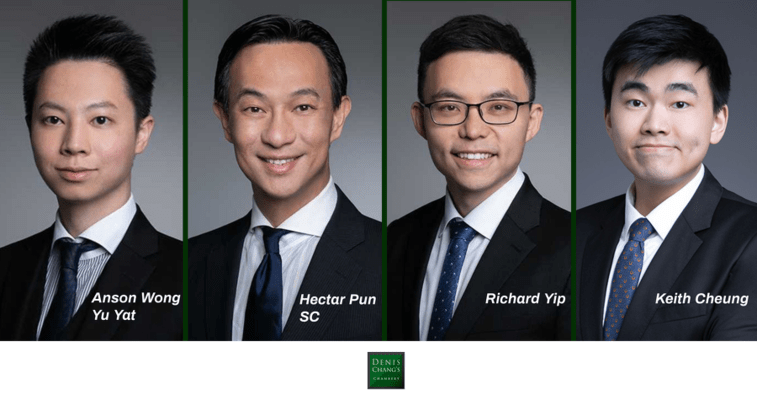

In recent months, decisions by the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong to cancel companies’ listings have been on the rise. During a live webinar on 3 September 2020, Hectar Pun SC, Richard Yip, Anson Wong Yu Yat and Keith Cheung shared their observations and practical experience on handling delisting proceedings before the Listing Committee and Listing Review Committee, and also on applying for judicial review as a last resort remedy.

Keith Cheung opened the presentation with a brief tour through the sequence of stages in the delisting process, covering the powers and functions of the Listing Committee and the relevant provisions in the Listing Rules, including the power to cancel or suspend trading.

Keith Cheung opened the presentation with a brief tour through the sequence of stages in the delisting process, covering the powers and functions of the Listing Committee and the relevant provisions in the Listing Rules, including the power to cancel or suspend trading.

A cancellation decision does not happen overnight. Keith commented on the trigger events which typically form the “prelude to a delisting decision”, such as the company’s failure to produce its financial report or repay its debts, which normally gives rise to a trading suspension. In gist, “it is typically the company’s failure to overcome suspension and meet the conditions for [trading] resumption” that sets in motion the delisting process, which begins with the Listing Division’s delivery of its report and recommendations to the Listing Committee.

Two sets of contrasting proceedings

Richard Yip, who has represented listed issuers (with Hectar Pun SC) in proceedings before the Listing Committee and the Listing Review Committee, shared his observations on the process.

Richard Yip, who has represented listed issuers (with Hectar Pun SC) in proceedings before the Listing Committee and the Listing Review Committee, shared his observations on the process.

After receiving the Listing Division’s report, the Listing Committee – the primary decision-making body – would hold an informal and non-adversarial meeting to reach a decision. The listed company would be informed of the outcome by letter a few days later.

“In our experience, the Listing Committee usually adopts the Listing Division’s recommendations [to delist or not],” explains Richard. “What’s notable is that the listed issuer has very little involvement or direct communication with the Listing Committee, and there is no opportunity to comment on the Listing Division’s recommendations.”

Issuers could request for a review of the delisting decision by the Listing Review Committee (“LRC”) within seven business days. In contrast with proceedings before the Listing Committee, the hearing of the LRC is held de novo; this means the LRC will scrutinise all the evidence again to come to its own conclusion, rather than simply accepting the Listing Division’s report. Moreover, the review process is adversarial in nature, allowing oral submissions from both sides.

Since directors are permitted to attend the LRC hearing with a legal adviser, companies are advisable to engage legal counsel if the case involves difficult legal questions such as interpretation of the Listing Rules. “There will be many questions from Committee members about the company’s underlying issues, and it is important for the legal adviser to prepare directors for questioning.”

Judicial review complexities

Should the LRC decide to cancel the company’s listing, would judicial review be a viable remedy? The answer is not quite so straightforward. Hectar Pun SC embarked on the discussion by highlighting the tricky aspects that practitioners should note.

Should the LRC decide to cancel the company’s listing, would judicial review be a viable remedy? The answer is not quite so straightforward. Hectar Pun SC embarked on the discussion by highlighting the tricky aspects that practitioners should note.

On the potential grounds for judicial review, which include illegality, irrationality, procedural unfairness, and breach of a legitimate expectation or constitutional right, Hectar notes: “Bear in mind that, whether a certain ground is viable depends on the Stock Exchange’s reasons for the suspension or delisting, the reasons given by the LRC (if a review took place), and the evidence available to support the ground.”

Another important legal hurdle for judicial review applicants is the need to exhaust all available alternative remedies. Generally, this means that issuers cannot “bypass” the LRC and go straight to the Court of First Instance. However, in exceptional circumstances, it may be possible to depart from this rule.

“An example would be the argument that immediate intervention is required because the appeal tribunal has no jurisdiction or the proceedings are based on an obvious and fundamental error of law,” he points out. “But what would amount to that? That is the million-dollar question. The recent cases we handled demonstrates the difficulty of establishing this.”

Implications of Brightoil Petroleum case

Anson Wong Yu Yat continued the discourse by revisiting several key cases including the most recent judicial review decision in Brightoil Petroleum (Holdings) Ltd v SEHK Ltd [2020] HKCFI 1601, where he acted for the Applicant.

Anson Wong Yu Yat continued the discourse by revisiting several key cases including the most recent judicial review decision in Brightoil Petroleum (Holdings) Ltd v SEHK Ltd [2020] HKCFI 1601, where he acted for the Applicant.

This case bears a few interesting features. The Applicant had, without waiting for the LRC to finish its review, gone to the Courts to challenge the Listing Committee’s decision. It was argued that, in failing to give the Applicant or its advisers the opportunity to read and respond to the Listing Division’s report, the Listing Committee’s decision breaches the fundamental principle of procedural fairness.

What is more, in the Form 86A (notice of application for leave to seek judicial review), the company applied for a stay of the judicial review proceedings pending the outcome of the LRC review. This was done to address the tension between the need to be prompt in challenging decisions by judicial review, and the need to first exhaust alternative remedies.

Mr. Justice Coleman refused to grant a stay of proceedings. He held, among others, that there is no requirement to promptly challenge a decision which itself is subject to an alternative remedy; moreover, there is no systemic procedural unfairness in offering the listed issuer only one round of adversarial arguments before the LRC.

“The difficulty for the Applicant lies in the absence of evidence to support the allegation of systemic unfairness, even though companies are routinely denied the right to access and respond to the Listing Division’s report,” observes Anson. “Since the Court of First Instance’s decision in Brightoil Petroleum is not binding on another High Court judge, if there is a better case with better evidence, applying for judicial review may be considered.”

Get clients in shape

Proceedings before the Listing Committee and the LRC are akin to two lines of defence. “The LRC hearing offers a fair chance to persuade the Committee members not to cancel the company’s listing,” says Richard. “Bear in mind that it is necessary to get the company in shape before there is a chance of obtaining a positive decision. The Committee will be concerned about the overall health of the company in in terms of operations and financials.” If the delisting decision stands, judicial review will be the last remedy.

Could a company’s director defer all questions to the legal advisers during the LRC hearing? In terms of legal representation, when should companies consider requesting for the “one-legal-adviser rule” to be relaxed? Watch our webinar recording to find out the answers plus other useful tips shared by the four speakers.

If you would like to receive a copy of the presentation slide deck, please email our Practice Development Managers, Sonia Chan or Taylor Goodwin.

|

Hectar Pun SC

|

|

Richard Yip

|

|

Anson Wong Yu Yat

|

|

Keith Cheung

|

Disclaimer: This article does not constitute legal advice and seeks to set out the general principles of the law. Detailed advice should therefore be sought from a legal professional relating to the individual merits and facts of a particular case. Except as otherwise noted, the views expressed at Events are the views of the speakers only and do not represent the opinions of all other Members of DCC.